What actually is the human mind? What is its nature? And what is the relationship of the mind to the human brain? (1)

What are you as a human (Part 4)

In the previous post I addressed the issue of what it is that’s unique about us as human beings, summarising that humans are those with self-conscious minds and free will.

But ‘what exactly is the self-conscious mind?’ - ‘what is its fundamental nature?’ These were questions that were raised by the end of that previous post. Indeed, having thought quite a bit about our brains and also about our minds over previous posts (and having also gone some distance in distinguishing human minds from animal minds), in order to answer those questions, a prior but key question needs considering, namely ‘what is the relationship of the mind to the brain?’ If the mind is identical to the brain, then that answers the question(s) - the mind is the brain and is ultimately physical in nature. But if the mind is something distinct from the brain - even if its correlated in function - then it is something beyond just physical matter.

The Mind in the Media

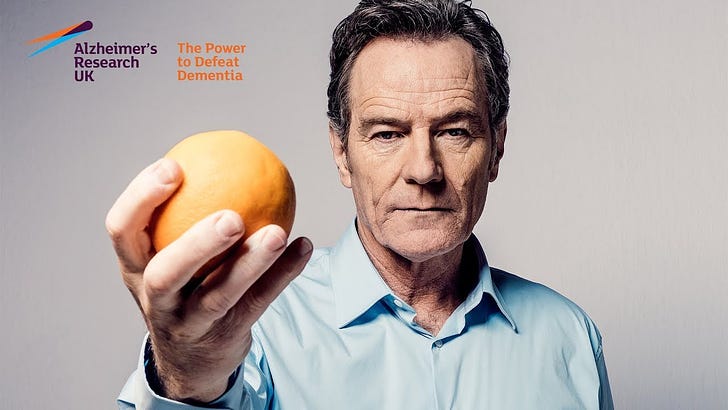

If you listen to much of what is said in the media, the assumption would seem to be that the mind and the brain are identical. Documentaries are regularly produced in which a doctor or a celebrity investigates the human brain, during which a human brain is held up of someone who’s died (and donated their brain for medical research), and the presenter then goes onto talk about how this brain used to be a person. Or youtube videos posted by the Alzheimers charity often express a similar belief – that as a person’s brain deteriorates, everything about that person deteriorates. The following clip would be an example:

The assumption of such media, and indeed by a selection of scientists, is that everything that you are - everything that it is to be human - is contained within the human brain; the mind and the brain are identical, they are one and the same thing. Because that is the view assumed in the media – the ‘identity-theorists’ getting most of the coverage – this is the view the average man-on-the-street assumes, that the mind and brain are identical. But those who are thinking more analytically about the question, aren’t so convinced.

Thinking more deeply about the Mind

Whilst popular among the man-on-street because of popular science and media, a lot of neuroscientists and philosophers think this identity-thesis is inaccurate. Because if you think carefully about mental states (states of the mind) and brain states (states of the brain), then actually it becomes evident that there are things that are true of mental states that are not true of brain states (and vice versa), therefore mental states can’t be identical to brain states. If something is true of A, that is not true of B, then A cannot be identical to B, they have to be distinct entities. Returning to those differences in a minute, the sentence articulated above should help us to see that the mind-brain question is not a scientific question but is actually a philosophical one. All careful thinkers recognise and celebrate what the neuroscience tells us, yet different thinkers have divergent philosophical interpretations of that neurological data - but the data itself being empirically equivalent across all those leading philosophical interpretations. Certain thinkers will often assume that because there is correlation between brain and mental states, they have to be the same thing, but leading philosophers of mind (such as David Chalmers, Yujin Nagasawa, John Searle, Thomas Nagel) and likewise leading (philosophically-attuned) neuroscientists (such as Roger Sperry, Mario Beauregard, John Eccles and Wilder Penfield [the latter hailed as the father of modern day neuroscience]) have come to different conclusions based on the realisation that there are some things true of mental states that aren’t true of brain states, so the mind can’t be identical to the brain.

‘Intentionality’ of mental states

Take for instance what’s called the ‘intentionality’ – the object-directedness - of a thought. When someone has a thought, they think about or of something. You might think of your friend, you think about your garden, you think of your holiday; The mental state is about or of something. But the associated brain state (the region in your brain for processing the thought) isn’t about anything at all. It just is - the neurons are just firing. The mental state is about something, the brain state isn’t, so we see a difference between brain states and mental states.

‘Qualia’

Or take what’s technically described as the ‘qualia’ of a sensation – the ‘what it is like’-ness to be (for example) experiencing a sensation of happiness. We could put the brain scanner on your head and see which neurons are firing when you’re having a sensation of happiness, but only you yourself would be able to know ‘what it is like’ to be experiencing that sensation. Or the same with pain; although we could see by looking at your (neurologically accessible) brain that you are in pain, only you yourself would know exactly what that (mental) sensation of pain is like – that ‘what it is like’-ness being specific to your mental state.1

The Mind being different to the brain

So there are things true of our mental states that are not true of our brain states, therefore our mental states are not identical to our brain states, and our mind is not identical to our brain. This is interesting because it means that our mind is not ultimately physical, but what exactly is, then, the mind and it’s nature? The forthcoming posts will explore.

The classic formulation of this argument was articulated by Thomas Nagel in his ‘What Is It Like to be a bat’, The Philosophical Review 83 (1974): 45-50. Nagel there argues that humans might know, from our third person scientific perspective, everything there is to know about a bat; we might know how its sonar radar system works, the length of time it can glide without flapping its wings, the intricate details of what occurs in its brain - we could know from a third person perspective everything there is to know about a bat - but we could never know what it’s actually like to be a bat.